Part 1: How soundbite culture has shaped our society

The 1980s: Campaign ads, catchphrases, and the birth of the 8-second soundbite

This piece is the first in a five-part series tracing the evolution of soundbite culture and how it’s shaped the way we consume information, debate ideas, and trust (or don’t trust) the media. Each decade tells a different part of the story. This series starts with the 1980s, when political campaigns, corporate advertising, and media consolidation collided to shrink our attention spans post-Cronkite era journalism. From there, I’ll look at the 1990s tabloid boom and reality-TV era, the rise of the internet in the 2000s, the weaponization of social media in the 2010s, and finally, the algorithm-driven attention economy of today. Together, these chapters reveal not only how our media ecosystem has transformed, but how it’s changed our society and psychology at the same time.

The death of critical thinking

Debates, in all forms, used to hinge on facts, context, and persuasion. Now, facts themselves are treated as weapons, used only when they reinforce the arguer’s side, and often dismissed as “fake news” when they don’t.

We now duel through social media memes, TikToks, emojis, and comment chains–often sharing outrageous content before verifying it. Think about the evolution of presidential debates, for instance. Complex policy questions have become condensed into soundbites like “eating cats” and “woke slurs,” and later recirculated as punchlines and weaponized in both mainstream news media and social media discussions.

Whether the platform is a presidential debate stage or a Facebook post, there’s become a staunch refusal to admit when one side has more to learn. Disagreements based on opinion are nothing new, but when facts collide with beliefs, acknowledgement now gets replaced by deflection, denial, and a culture of gaslighting that turns every exchange into a battle for dominance rather than understanding.

This culture continues to divide society, leaving us walking on eggshells in all facets of our life. But this extreme polarization isn’t an accident—it’s the logical endpoint of 40 years of shrinking conversations into slogans and memorable phrases to appeal to soundbite culture.

The most recent presidential debates are the culmination of that trajectory. Instead of policy detail about what each candidate would actually do, we got viral fodder: a claim that Haitian migrants were “eating pets,” vaping political outrage across feeds. Moments like that become memes, not lessons or follow ups on the fact checks that surround them. As a result, the truth gets weaponized or buried entirely…begging the question, how the f did we get here, and where the f are we headed?

How did we get here?

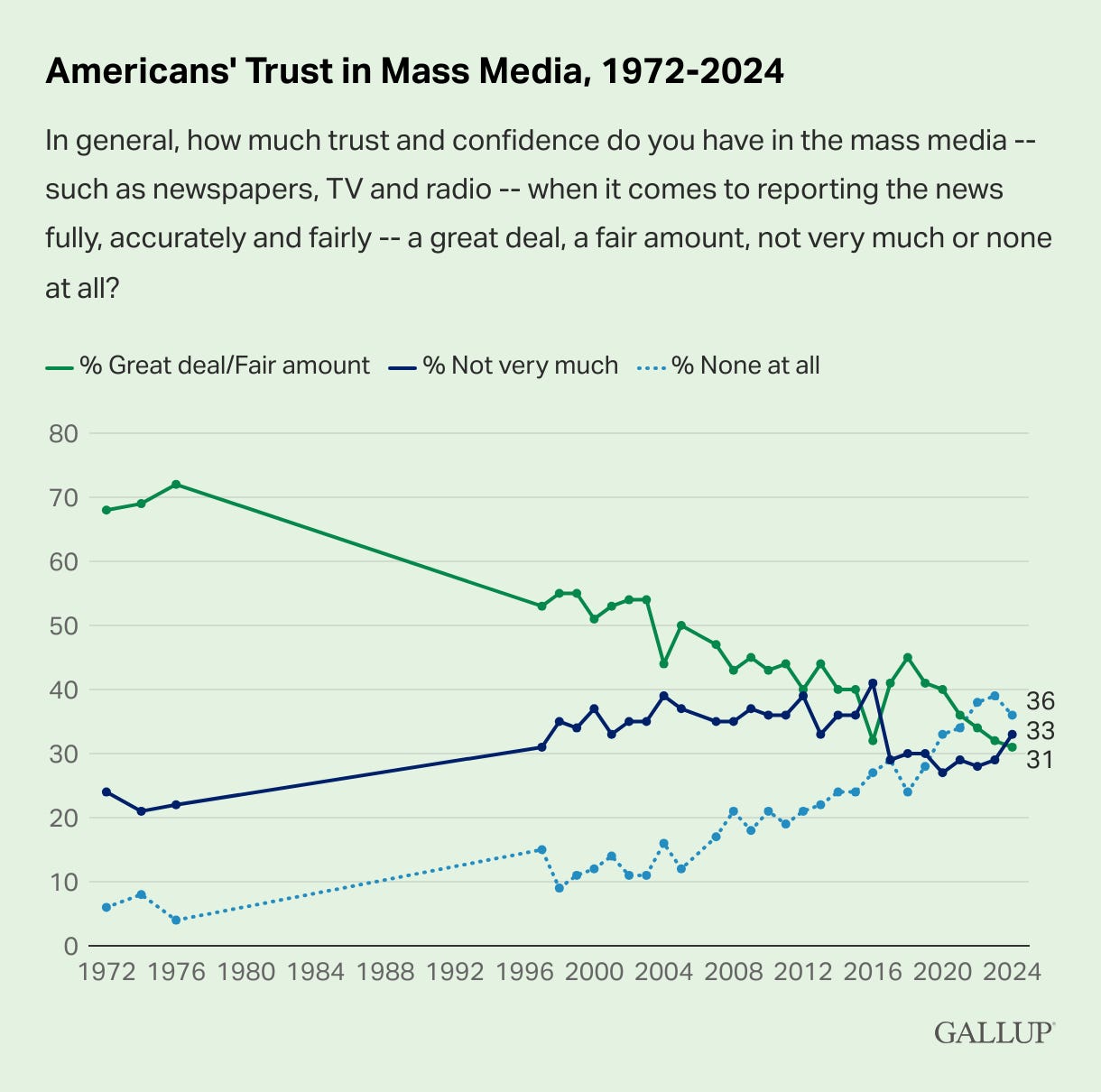

Once upon a time, Walter Cronkite closed his nightly broadcast with “And that’s the way it is.” And most Americans believed him. In 1976, a Gallup poll found that 72% of Americans trusted the media to report “fully, accurately, and fairly.” In 2024, Gallup found that number is now at just 31%. Trust didn’t vanish overnight. As visualized in the chart below, Gallup conducted that poll year after year, revealing that trust in news media was slowly declining over time. But as it was unraveling piece by piece, something else was gradually increasing to keep viewers engaged: soundbite culture.

To understand how we got to this point, let’s look back at the moments that reshaped how the “gatekeepers” packaged information and how we consumed it.

The 1980s: Campaign ads and the birth of the modern soundbite

If the 1960s and 70s were the age of in-depth coverage, the 1980s were the age of packaging it for views. Hence, the birth of the ‘news package’ that any modern journalism student knows exactly how to deliver. In the Walter Cronkite era, a candidate’s words often aired in full, sometimes 40 seconds or longer, according to 1992 research from Daniel C. Hallin, published in the Journal of Communication. Viewers got context, nuance, and the reasoning behind an argument. But by the late 1980s, that window shrunk to under 10 seconds on the evening news. News packages no longer showed the whole argument. They showed you the soundbite. And candidates quickly learned to speak in soundbites–a core element of modern media training.

Political consultants mastered the art of distilling entire platforms into phrases like:

Ronald Reagan’s 1980 debate question: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” became a single line that reframed the entire election.

George H.W. Bush’s 1988 pledge: “Read my lips: no new taxes.” stuck longer than any policy detail, for better or worse.

Even Wendy’s 1984 tagline “Where’s the beef?” bled into politics in soundbite form when Democratic candidate Walter Mondale used it in a primary debate to mock rival Gary Hart’s “new ideas” as all bun and no substance.

Outside politics, advertising doubled down on this trend. Nike told us to “Just do it.” The Army urged us to “Be all you can be.” The Milk Board promised “It does a body good.” Short, sharp, memorable. In practically every sphere of influence–commerce, politics, culture–the soundbite became the product.

But the impact on journalism was profound. With campaigns scripting daily talking points, reporters had little choice but to repeat them. As communication scholar Daniel Hallin documented, TV news was offering less context and more catchphrases. In practice, that meant a filtered, superficial picture of both candidates and issues.

And while the soundbites got shorter, trust got weaker. As shown in the Gallup chart above, by the mid-1980s, the number of Americans who believed the press “gets the facts straight” was already slipping. Viewers sensed they were no longer getting the full story, just the lines designed to play best on TV. The 1980s made it clear that brevity wasn’t just a style of communication, it was becoming the standard for gaining attention and likability.

At the same time, the media landscape itself was changing. The 1980s marked the start of a wave of media consolidation, as corporations began buying up newspapers, TV networks, and radio stations. With fewer independent outlets and more pressure to drive profits, coverage leaned increasingly toward sensationalism. Headlines and segments that would attract the largest audiences and biggest ad dollars could be found above the fold or in the A-block. This shaped the decision behind which stories aired and further eroded public trust, as viewers sensed that news was becoming less about informing the public and more about competing for attention.

But while the 1980s may have given birth to the modern soundbite, this was only its beginning. Over the next four decades, the spectacle would get louder, the stories shallower, the headlines more dramatic, and our attention spans shorter. In the next installment of this series, I’ll look at the 1990s–a wild and shocking (!) time when reality TV, tabloids, and cable news began to merge entertainment with journalism, training audiences to crave the dramatic clip more than the context around it.

From there, I’ll analyze the implications of the internet boom, the rise of social media, and the fractured, polarized, meme-flooded, brain-rotting all-encompassing media environment we’re living in now.

Because to understand how we ended up debating through memes and comments instead of in arguments, empathy, and ideas, we need to take a look at the major media moments and shifts that got us to this point, decade after decade.

Subscribe to get each part of the five-part series—part two coming soon…